A complex, evolving relationship, and the need to create a supportive environment

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the healthcare space and its livelihoods by forcing an industry-wide switch to digital care delivery models. This notion that care can be delivered remotely by moving some tasks from healthcare professionals to patients and caregivers is a seismic shift in the culture of the healthcare sector and its workforce.

This latest trend in healthcare of using information technology will only accelerate by consumer expectations and rapid technologic advancements such as robotics and artificial intelligence. In this new era of digital health transformation, healthcare employees are expected to work better and deliver more. Given this dynamic transformation of healthcare delivery, healthcare professionals are confronted with continuing changes in psychosocial working conditions of skills absence, increasing workload and complexity of task.

Current State of the Healthcare Environment

September 2022 marked the largest strike of private-sector nurses in U.S. history when 15,000 nurses walked out in Minnesota to protest understaffing and overworking (Gurley, 2022). According to the American Hospital Association (AHA), there will be a loss of 500,000 clinical professionals by the end of the year. One in five health care workers have left medicine since the COVID-19 pandemic began (Durbin, 2022).

Along with staffing shortages, the sheer stress and mental anguish of the caring profession was punctuated by the suicide of Dr. Lorne Breen, Dr. Radhika Lal Snyder, Michael Odell, RN, and countless others, including clinicians in residency.

What’s more, healthcare workers are four times more likely to experience workplace violence. Nearly 50% of emergency physicians say they’ve been assaulted and 70% of emergency nurses report being hit or kicked on the job (Budd, 2020). A recent study by WELL Health of clinical support staff, who are primarily responsible for communicating and coordinating with patients, found 88% moderate to extreme burn out, and concluded that patient care quality is directly linked to how clinical support staff experience their job (Well Health, 2021).

Environment, Work Stressors and Digital Stress

The health effects of work stressors contribute directly to whether any human can sustain a healthy sense of well-being. Research indicates that stress alone accounts for a variety of health issues including high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, depression, acute injuries, substance abuse and more. All this impacts the workplace, resulting in increasing turnover, absenteeism, burnout, lower performance, and workers’ compensation injuries.

The arduous training and professional commitment required of healthcare workers put them at higher risk of mental disorders, especially anxiety, depression, and burnout, as noted in overwhelming research findings from the pre-pandemic era. It is estimated that 30% of front-line health workers develop behavioral health conditions including, but not limited to, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as compared with 20% in the general population (Abbot et al., 2015). Brooks et al. found that long work hours in demanding circumstances, and not taking a day off each week, lead to fatigue, mental distress, job dissatisfaction and subjective health complaints.

The pandemic, disasters or public health emergencies have longstanding implications on healthcare professionals. Dealing with serious injuries or bodies of the dead results in a higher probability of developing PTSD, depression, alcohol problems, anxiety, stress, and fatigue symptoms as further evidenced by Brooks et al. Low perceived safety was associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety and other psychiatric symptoms (Brooks et al., 2016).

With the growing use of digital technology in care settings, the roles and responsibilities of the health workforce are transforming in an unprecedented manner. Health professionals are recognized as a key factor in the digital transformation of the health care sector. As digital technologies are embedded into everyday routines and environments, we must confront the concern of “technostress.” This digital stress as defined by Bondanini, et al. is a “negative psychological state related to current or future use (or abuse) of technology and commonly associated with an individual’s role in the workplace.” This stress includes the tasks the individual is assigned to perform with technology as part of that role. The consequences of digital stress are physiological, psychosocial, organizational, and societal (Bondanini et al., 2020). Workers can develop physical health problems and psychosocial problems like anxiety, job dissatisfaction, decreased work engagement. And this can lead to mental exhaustion or self-belief of incompetence (Bondanini et al., 2020). It is important to note that poor digital health literacy is the most common barrier to the digital reform of healthcare on both the clinical and patient sides.

A Call to Action: What Can We Do Now?

A cooperative effort between organizational leadership and healthcare professionals is needed to foster an environment that protects the wellbeing of healthcare professionals. A healthy workplace would provide appropriate training and ensures the resiliency of its workforce by shielding them from overwork and excessive stress and supporting them to seek help when needed.

Healthcare professionals can carry the weight of their own safety and well-being as well as those they serve. Making programmatic changes to educate, offer support and protect their health and well-being would reduce the risk of burnout, fatigue, or other behavioral health issues associated with being overworked, uncertain, or stressed. By better identifying who’s at higher risk, leaders can make better decisions in creating a safe, supportive workplace.

- Evaluate: Develop and conduct a survey to identify what health risks need to be addressed. What does your workforce need? What are the daily struggles they face? Effective intervention must operate across multiple levels, bottom-up (as opposed to top-down) approach. Interventions should be theoretically informed and involve experts.

- Examine the workplace environment: Does your work environment support a healthy workforce? Work upstream on the issues.

- View job/role design: Control over-work, overtime, number of hours worked, and access to social support, etc.

- What are the barriers or challenges that make it difficult for employees to practice healthy behaviors? Again, work upstream on issues pushing beyond physical fitness realms.

- Educate: Bring in external experts from psychology, racial inequality, well-being, diversity, equity and inclusion. And discuss issues like the impact of racial trauma and injustice, emotional labor, violence and more to help the healthcare workforce better understand emotional trauma. Invest in taking care of employees’ technical skills to avoid technostress. All staff must be educated on methods for coping with technology overload. Help them learn new skills as tech evolves.

- What skills do we value as an organization?

- What skills does the workforce need to thrive in their role now?

- What skills does the workforce need to thrive in their role in the future?

- Build: Establish community partnerships with state and local government agencies, colleges and universities, national nonprofit organizations, counseling centers, churches, youth groups, social service agencies, and advocacy organizations. Leadership must also build community by creating a climate of tolerance that allows employees to speak up. It’s important for workplace culture to encourage peers to engage in respectful conversations and respectful disagreements when needed. Leadership must talk openly about safety, well-being and healthy behaviors.

- Do workers let you know about mistakes, upsets or when things go wrong?

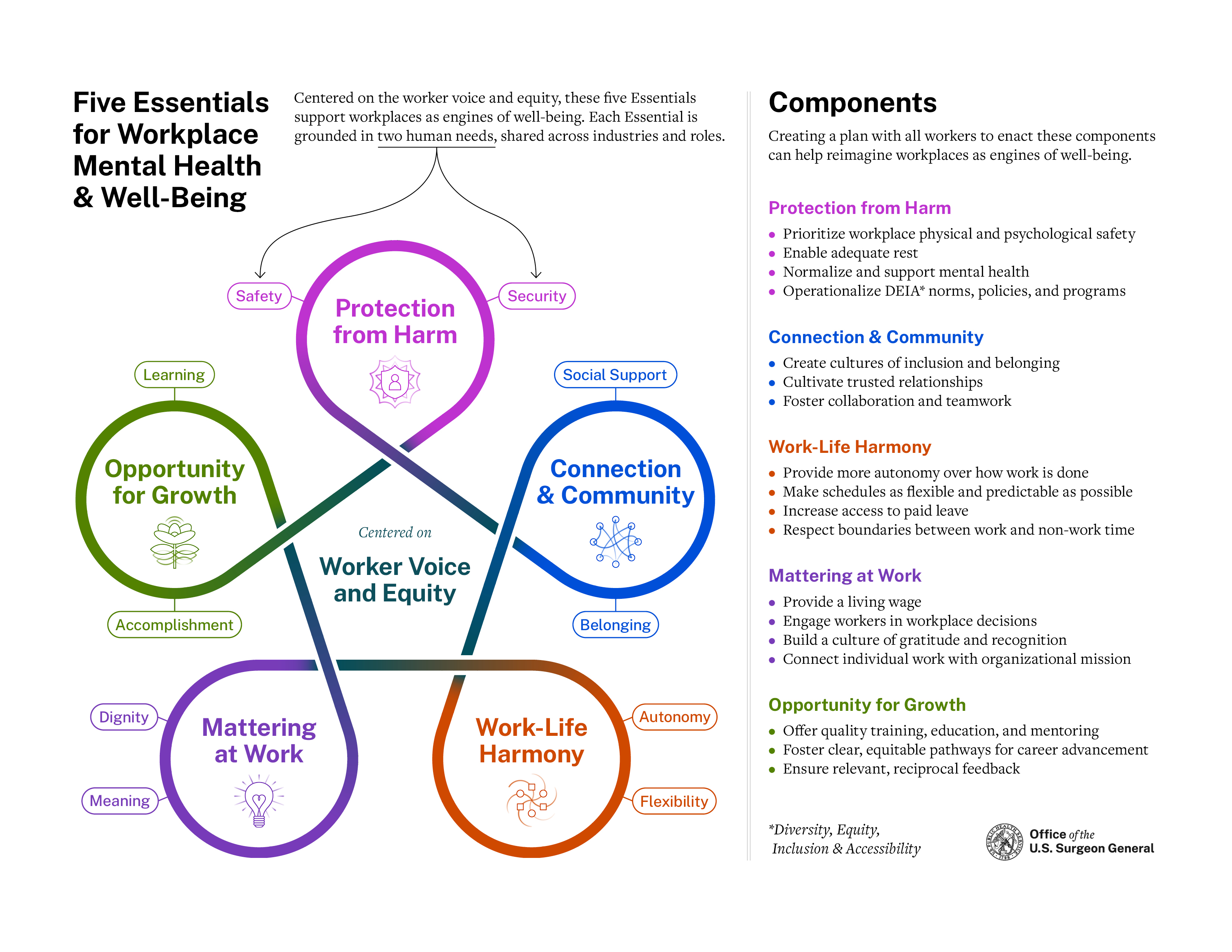

- Follow: On October 20, 2022, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy, released five components of a healthy workplace stating that, "Organizational leaders, managers, supervisors, and workers alike have an unprecedented opportunity to examine the role of work in our lives and explore ways to better enable all workers to thrive within the workplace and beyond." As the USA’s top doctor, his message serves as a national call to action for the public health issue of workplace stress. This framework provides a guidelines to creating a supportive environment so that healthcare professionals can experiences physical and psychological safety. By following these steps – while digital transformation rapidly alters the healthcare atmosphere – the workforce can be provided the chance to thrive in a healthier environment.

Source: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/workplace-mental-health-well-being.pdf

References

Aiken, L., Sloane, D., Clarke, S., Poghosyan, L., Cho, E., You, L., Aungsuroch, Y. (2011, May 11). Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/23/4/357/1802967

Bondanini, G., Giorgi, G., Ariza-Montes, A., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Andreucci-Annunziata, P. (2020, October 30). Technostress dark side of technology in the workplace: A scientometric analysis. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7662498/#B46-ijerph-17-080…

Brooks, S. K., Dunn, R., Amlôt, R., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2016). Social and occupational factors associated with psychological distress and disorder among disaster responders: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0120-9

Budd, K. (2020, February 24). Rising violence in the emergency department. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/rising-violence-emergency-department

Cord, A., Barber, E., Burke, B., & Harvey, J. (2015, April 21). What's killing our medics? Retrieved October 22, 2022, from http://www.revivingresponders.com/originalpaper

Durbin, R. (2022, September 16). The Medical Crisis We Can Fix. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://thehill.com/opinion/congress-blog/3646473-the-medical-crisis-we…

Gurley, L. (2022, September 12). Largest private-sector nurses strike in U.S. history begins in Minnesota. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/09/12/minnesota-nurses-str…

Longhini, J., Rossettini, G., & Palese, A. (2022, August 18). Digital Health Competencies among health care professionals: Systematic review. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.jmir.org/2022/8/e36414

Well Health. (2021, October 14). Study: 88% of Clinical Support Staff Experiencing Significant Burnout. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/study-88-of-clinical-support-s…